Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Looking for Medicare coverage?

Childhood Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumors Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

General Information About Childhood Central Nervous System (CNS) Germ Cell Tumors

Primary brain tumors, including germ cell tumors (GCTs), are a diverse group of diseases that together constitute the most common solid tumors of childhood. The most recent World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Central Nervous System Tumours implements some molecular parameters, in addition to histology, to define brain tumor entities.[

CNS GCTs are broadly classified as germinomatous (commonly referred to as germinoma) and nongerminomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs) on the basis of clinicopathological and laboratory features, including tumor markers.[

The PDQ childhood brain tumor treatment summaries are organized primarily according to the WHO Classification of Central Nervous System Tumours.[

Incidence

In Western countries, GCTs represent 3% to 4% of primary brain tumors in children, with a peak incidence from age 10 to 19 years.[

Overall, males have a higher incidence of GCTs than females. Male patients have a preponderance of pineal-region primary tumors.[

Anatomy

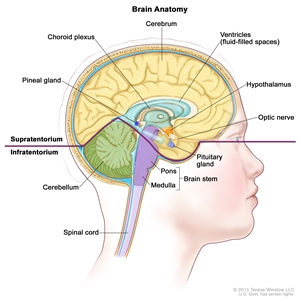

CNS GCTs usually arise in the pineal and/or suprasellar regions of the brain as solitary or multiple lesions (see Figure 1). The most common site of origin is the pineal region (45%), and the second most common site is the suprasellar region (30%) within the infundibulum or pituitary stalk. Both of these sites are considered extra-axial or nonparenchymal CNS locations. Approximately 5% to 10% of patients present with synchronous tumors arising in both the suprasellar and pineal locations. Germinoma is the most frequently observed histology.[

Figure 1. Anatomy of the inside of the brain. The supratentorium contains the cerebrum, ventricles (with cerebrospinal fluid shown in blue), choroid plexus, hypothalamus, pineal gland, pituitary gland, and optic nerve. The infratentorium contains the cerebellum and brain stem.

Clinical Features

The signs and symptoms of CNS GCTs depend on the location of the tumor in the brain, as follows:

- Suprasellar region. Patients with tumors arising in the suprasellar region often present with subtle or overt hormonal deficiencies and may experience a protracted prodrome lasting months to years. Diabetes insipidus caused by antidiuretic hormone deficiency occurs in 70% to 90% of patients and is the most common sentinel symptom. Patients can usually compensate for this deficiency by drinking excessive amounts of fluid for months to years. Eventually, other hormonal symptoms and visual deficits may emerge as the tumor expands dorsally and compresses or invades the optic chiasm and/or fills the third ventricle to cause hydrocephalus.[

14 ,15 ,16 ] - Pineal region. Patients with tumors in the pineal region usually have a shorter history of symptoms than patients with tumors of the suprasellar or basal ganglionic region, with weeks to months of symptoms that include raised intracranial pressure and diplopia related to tectal and aqueductal compression. Signs and symptoms unique to masses in the pineal and posterior third ventricular region include Parinaud syndrome (vertical gaze impairment, convergence nystagmus, and light-near pupillary response dissociation), headache, and nausea and vomiting.

- Bifocal tumors. Patients with bifocal primary tumors present with metasynchronous lesions in the suprasellar and pineal regions.[

15 ] The secondary lesion is often asymptomatic and found on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In children with pineal primary tumors, the suprasellar lesion may also be associated with unexplained precocious puberty.

Nonspecific symptoms such as enuresis, anorexia, and psychiatric complaints [

Diagnostic Evaluation and Prognostic Factors

Radiographic characteristics of CNS GCTs cannot reliably differentiate germinomas from NGGCTs or other CNS tumors. The diagnosis of GCTs is based on the following:

- Characteristic clinical signs and symptoms supported by neuroimaging.

- GCT marker analysis in the serum and lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

- Histology, if necessary.

The diagnosis of a suspected CNS GCT and an assessment of the clinical deficits and extent of metastases can usually be confirmed with the following tests:

- MRI of brain and spine with and without gadolinium.

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and beta subunit human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-HCG) levels in both serum and CSF, and cytology, if needed. If preoperative CSF can be obtained safely and tumor markers are found to be elevated, histological confirmation may not be needed. Before definitive therapy is initiated, a lumbar CSF assessment for cytology and tumor markers should be performed, if safe, to reconfirm the diagnosis and help monitor treatment response and control. The diagnostic utility of lumbar CSF is better validated and more reliable than that obtained from the ventricles (see Table 1).[

18 ,19 ] - Evaluation of pituitary/hypothalamic function.

- Visual-field and acuity examinations for suprasellar or hypothalamic tumors.

If possible, a baseline neuropsychological examination should be performed after symptoms of endocrine deficiency and raised intracranial pressure are resolved.

CNS GCTs can be diagnosed and classified on the basis of histology alone, tumor markers alone, or a combination of both.[

Distinguishing between different GCT types by CSF protein marker levels alone is somewhat arbitrary, and standards vary across continents. Patients with pure germinomas and teratomas usually present with negative markers, but low levels of beta-HCG can be detected in patients with germinomas.[

The use of tumor markers and histology in GCT clinical trials is evolving. For example, in the COG-ACNS1123 (NCT01602666) trial, patients were eligible for assignment to the germinoma regimen without biopsy confirmation if they had one of the following:

- Either pineal region tumors or suprasellar primary tumors, normal AFP levels, and beta-HCG levels between 5 and 50 IU/L in serum and/or CSF.

- Bifocal (pineal and suprasellar) involvement or pineal lesions with diabetes insipidus, normal AFP levels, and beta-HCG levels of 100 IU/L or lower in serum and/or CSF.

| Tumor Type | Beta-HCG | AFP | PLAP | c-kit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP = alpha-fetoprotein; HCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; PLAP = placental alkaline phosphatase; + = positive; +++ = highly positive (elevated); - = negative; ± = equivocal. | |||||

| Germinoma | ± | - | ± | + | |

| Germinoma (syncytiotrophoblastic) | + | - | ± | + | |

| Embryonal carcinoma | ± | + | ± | - | |

| Yolk sac tumor | - | +++ | ± | - | |

| Choriocarcinoma | +++ | - | ± | - | |

| Teratoma | |||||

| Immature teratoma | ± | ± | - | ± | |

| Immature teratoma with malignant components | ± | + | + | ± | |

| Mature teratoma | - | - | - | - | |

| Mixed germ cell tumor | ± | ± | ± | ± | |

There is also an effort to use tumor markers to determine prognosis on the basis of the presence and degree of elevation of AFP and beta-HCG. This is an evolving process, and cooperative groups in North America, Europe, and Japan have adopted slightly different criteria.[

Alternative classification schemes for CNS GCTs have been proposed by groups such as the Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group for CNS GCTs. This group based their stratification on the prognostic grouping of the differing histological variants, as shown in Table 2.[

| Prognostic Group | Tumor Type |

|---|---|

| Good | Germinoma, pure |

| Mature teratoma | |

| Intermediate | Germinoma with syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells |

| Immature teratoma | |

| Mixed tumors mainly composed of germinoma or teratoma | |

| Teratoma with malignant transformation | |

| Poor | Choriocarcinoma |

| Embryonal carcinoma | |

| Mixed tumors mainly composed of choriocarcinoma, yolk sac tumor, or embryonal carcinoma | |

| Yolk sac tumor |

It is crucial that appropriate staging is determined and that germinomas are distinguished from NGGCTs. Chemotherapy and radiation treatment plans differ significantly depending on GCT category and extent of disease.

Cellular and Molecular Classification

The pathogenesis of intracranial GCTs is unknown. The germ cell theory proposes that CNS GCTs arise from primordial germ cells that have aberrantly migrated and undergone malignant transformation. A genome-wide methylation profiling study of 61 GCTs supports this hypothesis.[

An alternative hypothesis, the embryonic cell theory, proposes that GCTs arise from a pluripotent embryonic cell that escapes normal developmental signals and progresses to CNS GCTs.[

The WHO has classified CNS GCTs into the following groups:[

- Germinoma.

- Nongerminomatous GCTs.

- Embryonal carcinoma.

- Yolk sac tumor.

- Choriocarcinoma.

- Teratoma.

- Mature teratoma.

- Immature teratoma.

- Teratoma with somatic-type malignancy.

- Mixed GCT.

NGGCTs can consist of one malignant NGGCT type or contain multiple elements of GCT components, including teratomatous or germinomatous constituents.

Recurrent variants in KIT, genes in the MAPK pathway, and genes in the PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway have been identified in CNS GCTs.[

In a retrospective analysis of 82 children and adults with CNS GCTs, chromosome 12p gain was the most frequent copy number alteration. 12p gain was more frequent in NGGCTs (20 of 40, 50%) than germinomas (5 of 42, 12%). 12p gain was associated with worse survival in patients with NGGCTs (10-year overall survival rate, 47% for patients with 12p gain vs. 90% without; P = .02).[

Global hypomethylation that mirrors primordial germ cells in early development has also been observed in CNS GCTs.[

In an evaluation of 21 cases of CNS germinomas diagnosed between 2000 and 2016, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Ninety percent of germinomas had germ cell components that stained positively for PD-L1. In addition, tumor-associated lymphocytes stained positive for PD-L1 in more than 75% of cases.[

References:

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al.: The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23 (8): 1231-1251, 2021.

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed.: WHO Classification of Tumours: Central Nervous System Tumours. Vol. 6. 5th ed. IARC Press; 2021.

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD: WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th rev.ed. IARC Press, 2016.

- Matsutani M, Sano K, Takakura K, et al.: Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg 86 (3): 446-55, 1997.

- Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P, et al.: CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010-2014. Neuro Oncol 19 (suppl_5): v1-v88, 2017.

- Committee of Brain Tumor Registry of Japan: Report of Brain Tumor Registry of Japan (1969-1996). Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 43 (Suppl): i-vii, 1-111, 2003.

- The Committee of Brain Tumor Registry of Japan: Brain Tumor Registry of Japan (2001–2004). Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 54 (Suppl): 1-102, 2014.

Also available online . Last accessed August 21, 2023. - Weksberg DC, Shibamoto Y, Paulino AC: Bifocal intracranial germinoma: a retrospective analysis of treatment outcomes in 20 patients and review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82 (4): 1341-51, 2012.

- Matsutani M; Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group: Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for CNS germ cell tumors--the Japanese experience. J Neurooncol 54 (3): 311-6, 2001.

- Goodwin TL, Sainani K, Fisher PG: Incidence patterns of central nervous system germ cell tumors: a SEER Study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31 (8): 541-4, 2009.

- Villano JL, Propp JM, Porter KR, et al.: Malignant pineal germ-cell tumors: an analysis of cases from three tumor registries. Neuro Oncol 10 (2): 121-30, 2008.

- Koh KN, Wong RX, Lee DE, et al.: Outcomes of intracranial germinoma-A retrospective multinational Asian study on effect of clinical presentation and differential treatment strategies. Neuro Oncol 24 (8): 1389-1399, 2022.

- Graham RT, Abu-Arja MH, Stanek JR, et al.: Multi-institutional analysis of treatment modalities in basal ganglia and thalamic germinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68 (10): e29172, 2021.

- Kilday JP, Laughlin S, Urbach S, et al.: Diabetes insipidus in pediatric germinomas of the suprasellar region: characteristic features and significance of the pituitary bright spot. J Neurooncol 121 (1): 167-75, 2015.

- Hoffman HJ, Otsubo H, Hendrick EB, et al.: Intracranial germ-cell tumors in children. J Neurosurg 74 (4): 545-51, 1991.

- Sethi RV, Marino R, Niemierko A, et al.: Delayed diagnosis in children with intracranial germ cell tumors. J Pediatr 163 (5): 1448-53, 2013.

- Malbari F, Gershon TR, Garvin JH, et al.: Psychiatric manifestations as initial presentation for pediatric CNS germ cell tumors, a case series. Childs Nerv Syst 32 (8): 1359-62, 2016.

- Crawford JR, Santi MR, Vezina G, et al.: CNS germ cell tumor (CNSGCT) of childhood: presentation and delayed diagnosis. Neurology 68 (20): 1668-73, 2007.

- Allen J, Chacko J, Donahue B, et al.: Diagnostic sensitivity of serum and lumbar CSF bHCG in newly diagnosed CNS germinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59 (7): 1180-2, 2012.

- Rosenblum MK, Nakazato Y, Matsutani M: Germ cell tumours. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD: WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. 4th rev.ed. IARC Press, 2016, pp 286-91.

- Murray MJ, Bartels U, Nishikawa R, et al.: Consensus on the management of intracranial germ-cell tumours. Lancet Oncol 16 (9): e470-e477, 2015.

- Frazier AL, Olson TA, Schneider DT, et al.: Germ cell tumors. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, eds.: Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2015, pp 899-918.

- Calaminus G, Bamberg M, Harms D, et al.: AFP/beta-HCG secreting CNS germ cell tumors: long-term outcome with respect to initial symptoms and primary tumor resection. Results of the cooperative trial MAKEI 89. Neuropediatrics 36 (2): 71-7, 2005.

- Fukushima S, Yamashita S, Kobayashi H, et al.: Genome-wide methylation profiles in primary intracranial germ cell tumors indicate a primordial germ cell origin for germinomas. Acta Neuropathol 133 (3): 445-462, 2017.

- Schneider DT, Zahn S, Sievers S, et al.: Molecular genetic analysis of central nervous system germ cell tumors with comparative genomic hybridization. Mod Pathol 19 (6): 864-73, 2006.

- Sano K, Matsutani M, Seto T: So-called intracranial germ cell tumours: personal experiences and a theory of their pathogenesis. Neurol Res 11 (2): 118-26, 1989.

- Teilum G: Embryology of ovary, testis, and genital ducts. In: Teilum G: Special Tumors of Ovary and Testis and Related Extragonadal Lesions: Comparative Pathology and Histological Identification. J. B. Lippincott, 1976, pp 15-30.

- Wang L, Yamaguchi S, Burstein MD, et al.: Novel somatic and germline mutations in intracranial germ cell tumours. Nature 511 (7508): 241-5, 2014.

- Takami H, Fukuoka K, Fukushima S, et al.: Integrated clinical, histopathological, and molecular data analysis of 190 central nervous system germ cell tumors from the iGCT Consortium. Neuro Oncol 21 (12): 1565-1577, 2019.

- Schulte SL, Waha A, Steiger B, et al.: CNS germinomas are characterized by global demethylation, chromosomal instability and mutational activation of the Kit-, Ras/Raf/Erk- and Akt-pathways. Oncotarget 7 (34): 55026-55042, 2016.

- Satomi K, Takami H, Fukushima S, et al.: 12p gain is predominantly observed in non-germinomatous germ cell tumors and identifies an unfavorable subgroup of central nervous system germ cell tumors. Neuro Oncol 24 (5): 834-846, 2022.

- Wildeman ME, Shepard MJ, Oldfield EH, et al.: Central Nervous System Germinomas Express Programmed Death Ligand 1. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 77 (4): 312-316, 2018.

Stage Information for Childhood CNS Germ Cell Tumors

There is no universally accepted clinical staging system for germ cell tumors (GCTs), but a modified Chang staging system has traditionally been used.[

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In addition to whole-brain MRI, MRI of the spine is required.

- Lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). When medically permissible, lumbar CSF should be obtained for the measurement of tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein [AFP] and beta subunit human chorionic gonadotropin [beta-HCG]) and for cytopathological review.

Ventricular tumor markers are obtained for AFP and beta-HCG in the presence of obstructive hydrocephalus and a necessary CSF diversion. However, ventricular CSF does not serve as a substitute for CSF tumor staging and cytopathological review. Both serum and CSF tumor markers should be obtained for a thorough staging and diagnostic evaluation.[

2 ]

Patients with localized disease and negative CSF cytology are considered to be metastatic negative (M0). Patients with positive CSF cytology or patients with drop metastasis (spinal or cranial subarachnoid metastases) are considered to be metastatic positive (M+). Appropriate staging is crucial because patients with metastatic disease require extended radiation fields.

GCTs may be disseminated throughout the neuraxis at the time of diagnosis or at any disease stage. Several patterns of spread may occur in germinomas, such as subependymal dissemination in the lateral or third ventricles and parenchymal infiltration. Extracranial spread to lung or bone is rare but has been reported.[

References:

- Calaminus G, Kortmann R, Worch J, et al.: SIOP CNS GCT 96: final report of outcome of a prospective, multinational nonrandomized trial for children and adults with intracranial germinoma, comparing craniospinal irradiation alone with chemotherapy followed by focal primary site irradiation for patients with localized disease. Neuro Oncol 15 (6): 788-96, 2013.

- Fujimaki T, Mishima K, Asai A, et al.: Levels of beta-human chorionic gonadotropin in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with malignant germ cell tumor can be used to detect early recurrence and monitor the response to treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol 30 (7): 291-4, 2000.

- Jennings MT, Gelman R, Hochberg F: Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg 63 (2): 155-67, 1985.

- Gay JC, Janco RL, Lukens JN: Systemic metastases in primary intracranial germinoma. Case report and literature review. Cancer 55 (11): 2688-90, 1985.

Treatment Option Overview for Childhood CNS Germ Cell Tumors

Teratomas, germinomas, and other nongerminomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs) have differing prognoses and require different treatment regimens. Studies have observed the following:[

- For children older than 3 years and adults, radiation therapy has been an important component of therapy for germinomas and NGGCTs, although the optimal dose and field of irradiation are debated.

- Central nervous system (CNS) germ cell tumors (GCTs), similar to gonadal and extragonadal GCTs, have demonstrated sensitivity to chemotherapy.

- Germinomas are highly chemosensitive and radiosensitive tumors. They are curable with craniospinal irradiation and local site–boost radiation therapy alone. However, the use of neoadjuvant or preirradiation chemotherapy allows reduced radiation therapy doses and volumes and, subsequently, reduced long-term radiation therapy–related effects.

- In North America and Europe, patients with localized germinomas are effectively treated with whole-ventricular irradiation supplemented with tumor site–boost radiation therapy. Focal irradiation to the tumor bed, regardless of response to chemotherapy, is considered inadequate treatment.[

6 ] - For NGGCTs, the combined use of more intensive neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by either localized or craniospinal irradiation has resulted in improved survival rates in the last decade.[

5 ,7 ,8 ] - Patients with bifocal intracranial GCTs limited to the suprasellar and pineal region were treated in the same manner as patients with localized, nonmetastatic tumors in studies in North America and Europe.[

8 ]

Table 3 outlines the treatment options for patients with newly diagnosed and recurrent childhood CNS GCTs.

| Treatment Group | Treatment Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Newly diagnosed childhood CNS germinomas | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by response-based radiation therapy | |

| Radiation therapy | ||

| Newly diagnosed childhood CNS nongerminomatous GCTs | Chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy | |

| Surgery, if incomplete response to chemotherapy before irradiation | ||

| Newly diagnosed childhood CNS teratomas | Gross-total resection | |

| Recurrent childhood CNS GCTs | Chemotherapy followed by additional radiation therapy | |

| High-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue with or without additional radiation therapy | ||

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer. Between 1975 and 2010, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[

References:

- Osuka S, Tsuboi K, Takano S, et al.: Long-term outcome of patients with intracranial germinoma. J Neurooncol 83 (1): 71-9, 2007.

- Allen JC, Kim JH, Packer RJ: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed germ-cell tumors of the central nervous system. J Neurosurg 67 (1): 65-70, 1987.

- Kellie SJ, Boyce H, Dunkel IJ, et al.: Primary chemotherapy for intracranial nongerminomatous germ cell tumors: results of the second international CNS germ cell study group protocol. J Clin Oncol 22 (5): 846-53, 2004.

- Calaminus G, Kortmann R, Worch J, et al.: SIOP CNS GCT 96: final report of outcome of a prospective, multinational nonrandomized trial for children and adults with intracranial germinoma, comparing craniospinal irradiation alone with chemotherapy followed by focal primary site irradiation for patients with localized disease. Neuro Oncol 15 (6): 788-96, 2013.

- Fangusaro J, Wu S, MacDonald S, et al.: Phase II Trial of Response-Based Radiation Therapy for Patients With Localized CNS Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 37 (34): 3283-3290, 2019.

- Joo JH, Park JH, Ra YS, et al.: Treatment outcome of radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: adaptive radiation field in relation to response to chemotherapy. Anticancer Res 34 (10): 5715-21, 2014.

- Goldman S, Bouffet E, Fisher PG, et al.: Phase II Trial Assessing the Ability of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy With or Without Second-Look Surgery to Eliminate Measurable Disease for Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 33 (22): 2464-71, 2015.

- Calaminus G, Frappaz D, Kortmann RD, et al.: Outcome of patients with intracranial non-germinomatous germ cell tumors-lessons from the SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 trial. Neuro Oncol 19 (12): 1661-1672, 2017.

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Childhood CNS Germinomas

Treatment options for newly diagnosed childhood central nervous system (CNS) germinomas include the following:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by response-based radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy.

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Response-Based Radiation Therapy

Chemotherapy has been explored to reduce radiation therapy doses and associated neurodevelopmental morbidity. Several studies have confirmed the feasibility of this approach for maintaining excellent survival rates.[

Chemotherapy agents such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, etoposide, cisplatin, and carboplatin are highly active in CNS germinomas. Managing patients receiving chemotherapy agents that require hyperhydration (e.g., cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin) can be quite challenging because of the possibility of diabetes insipidus in patients with primary tumors of the suprasellar region.[

An international group of investigators explored a chemotherapy-only approach primarily for younger children. A complete response was achieved in 84% of patients with germinomas who were treated with chemotherapy alone. However, 50% of these patients suffered tumor relapse or progression. Many recurrences were local, local plus ventricular, and ventricular alone and/or with leptomeningeal dissemination throughout the CNS, which required additional therapy, including radiation.[

Subsequent studies have continued to support the need for radiation therapy after chemotherapy and the likely requirement for whole-ventricular irradiation (24 Gy) with local tumor site–boost radiation therapy (total dose, 40 Gy).[

Optimal management of bifocal lesions is less clear, but most investigators consider this presentation a form of metachronous primary disease to be staged as M0. A meta-analysis of 60 patients demonstrated excellent progression-free survival after craniospinal irradiation alone. Chemotherapy plus localized radiation therapy, including whole-ventricular irradiation, also resulted in excellent disease control.[

Results have been reported for the ACNS1123 (NCT01602666) phase II trial (stratum 2) that investigated response-based radiation therapy for localized germinomas. Patients were aged 3 to 21 years. Patients who had a complete response to carboplatin and etoposide chemotherapy received 18 Gy of whole-ventricle irradiation and a 12-Gy boost to the tumor bed. Patients who had a partial response to chemotherapy proceeded to receive 24 Gy of whole-ventricle irradiation and a 12-Gy boost to the tumor bed. Longitudinal cognitive functioning was evaluated prospectively. There were 137 eligible patients. Among 90 evaluable patients, 74 were treated with 18 Gy of radiation, and 16 were treated with 24 Gy of whole-ventricle irradiation.[

- The study failed to demonstrate noninferiority of the 18 Gy whole-ventricle irradiation regimen, compared with the study-specified threshold of a 95% 3-year PFS rate. The analysis was confounded by including any patient who could not be assessed for progression at 3 years as a treatment failure, which lead to a PFS rate of 86%. If these patients who could not be assessed were excluded, the Kaplan-Meier–based 3-year PFS estimates were 94.5% (± 2.7%) for the 18 Gy cohort.

- Collectively, estimated mean IQ, attention, and concentration were within normal range. A lower mean attention score was observed at 9 months for patients who were treated with 24 Gy of radiation. Acute effects in processing speed were observed for patients who were treated with 18 Gy at 9 months, which improved at the 30-month assessment. However, the sample size was small and did not account for confounding variables such as surgical complications, hydrocephalus, and limited long-term follow-up data.

- None of the evaluable patients had a relapse within the ventricular field or in the primary tumor region. All four disease progressions occurred outside of the radiation field, at a median time of 8.91 months after radiation therapy.

- Of the eight relapses, three occurred along the biopsy tract.

- Residual disease at the end of treatment was not associated with a worse prognosis.

A retrospective study from China included 161 patients with localized pure germinomas arising in the basal ganglia. Patients received whole-brain plus boost radiation therapy after induction chemotherapy. This treatment resulted in relapses in 4 of 109 patients. The disease-free survival rate was 97.2%. There were no differences in quality-of-life outcomes for adults who received focal or whole-brain radiation therapy. In contrast, the use of focal, tumor-only irradiation resulted in relapses in 15 of 35 patients.[

Radiation Therapy

CNS germinomas are highly radiosensitive and have been traditionally treated successfully with radiation therapy alone. Historically, patients with nondisseminated disease have been treated with craniospinal irradiation plus a boost to the region of the primary tumor. The dose of craniospinal irradiation has ranged from 24 Gy to 36 Gy, although studies have used lower doses. The local tumor dose of radiation therapy has ranged between 40 Gy and 50 Gy. Studies of lower-dose craniospinal irradiation have shown excellent outcomes.[

Patterns of relapse after craniospinal irradiation versus reduced-volume radiation therapy (whole-brain or whole-ventricular radiation therapy) have supported the omission of craniospinal irradiation for localized germinomas.[

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Newly Diagnosed Childhood CNS Germinomas

Early-phase therapeutic trials may be available for selected patients. These trials may be available via the

References:

- Calaminus G, Kortmann R, Worch J, et al.: SIOP CNS GCT 96: final report of outcome of a prospective, multinational nonrandomized trial for children and adults with intracranial germinoma, comparing craniospinal irradiation alone with chemotherapy followed by focal primary site irradiation for patients with localized disease. Neuro Oncol 15 (6): 788-96, 2013.

- Kretschmar C, Kleinberg L, Greenberg M, et al.: Pre-radiation chemotherapy with response-based radiation therapy in children with central nervous system germ cell tumors: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48 (3): 285-91, 2007.

- Allen JC, DaRosso RC, Donahue B, et al.: A phase II trial of preirradiation carboplatin in newly diagnosed germinoma of the central nervous system. Cancer 74 (3): 940-4, 1994.

- Buckner JC, Peethambaram PP, Smithson WA, et al.: Phase II trial of primary chemotherapy followed by reduced-dose radiation for CNS germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 17 (3): 933-40, 1999.

- Khatua S, Dhall G, O'Neil S, et al.: Treatment of primary CNS germinomatous germ cell tumors with chemotherapy prior to reduced dose whole ventricular and local boost irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55 (1): 42-6, 2010.

- Cheng S, Kilday JP, Laperriere N, et al.: Outcomes of children with central nervous system germinoma treated with multi-agent chemotherapy followed by reduced radiation. J Neurooncol 127 (1): 173-80, 2016.

- O'Neil S, Ji L, Buranahirun C, et al.: Neurocognitive outcomes in pediatric and adolescent patients with central nervous system germinoma treated with a strategy of chemotherapy followed by reduced-dose and volume irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57 (4): 669-73, 2011.

- Lee DS, Lim DH, Kim IH, et al.: Upfront chemotherapy followed by response adaptive radiotherapy for intracranial germinoma: Prospective multicenter cohort study. Radiother Oncol 138: 180-186, 2019.

- Afzal S, Wherrett D, Bartels U, et al.: Challenges in management of patients with intracranial germ cell tumor and diabetes insipidus treated with cisplatin and/or ifosfamide based chemotherapy. J Neurooncol 97 (3): 393-9, 2010.

- Balmaceda C, Heller G, Rosenblum M, et al.: Chemotherapy without irradiation--a novel approach for newly diagnosed CNS germ cell tumors: results of an international cooperative trial. The First International Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol 14 (11): 2908-15, 1996.

- da Silva NS, Cappellano AM, Diez B, et al.: Primary chemotherapy for intracranial germ cell tumors: results of the third international CNS germ cell tumor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54 (3): 377-83, 2010.

- Alapetite C, Brisse H, Patte C, et al.: Pattern of relapse and outcome of non-metastatic germinoma patients treated with chemotherapy and limited field radiation: the SFOP experience. Neuro Oncol 12 (12): 1318-25, 2010.

- Abu-Arja MH, Shatara MS, Okcu MF, et al.: The role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the management of metastatic central nervous system germinoma: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 70 (10): e30601, 2023.

- Weksberg DC, Shibamoto Y, Paulino AC: Bifocal intracranial germinoma: a retrospective analysis of treatment outcomes in 20 patients and review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82 (4): 1341-51, 2012.

- Graham RT, Abu-Arja MH, Stanek JR, et al.: Multi-institutional analysis of treatment modalities in basal ganglia and thalamic germinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68 (10): e29172, 2021.

- Bartels U, Onar-Thomas A, Patel SK, et al.: Phase II trial of response-based radiation therapy for patients with localized germinoma: a Children's Oncology Group study. Neuro Oncol 24 (6): 974-983, 2022.

- Li B, Feng J, Chen L, et al.: Relapse pattern and quality of life in patients with localized basal ganglia germinoma receiving focal radiotherapy, whole-brain radiotherapy, or craniospinal irradiation. Radiother Oncol 158: 90-96, 2021.

- Bamberg M, Kortmann RD, Calaminus G, et al.: Radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: results of the German cooperative prospective trials MAKEI 83/86/89. J Clin Oncol 17 (8): 2585-92, 1999.

- Shibamoto Y, Abe M, Yamashita J, et al.: Treatment results of intracranial germinoma as a function of the irradiated volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 15 (2): 285-90, 1988.

- Cho J, Choi JU, Kim DS, et al.: Low-dose craniospinal irradiation as a definitive treatment for intracranial germinoma. Radiother Oncol 91 (1): 75-9, 2009.

- Huang PI, Chen YW, Wong TT, et al.: Extended focal radiotherapy of 30 Gy alone for intracranial synchronous bifocal germinoma: a single institute experience. Childs Nerv Syst 24 (11): 1315-21, 2008.

- Eom KY, Kim IH, Park CI, et al.: Upfront chemotherapy and involved-field radiotherapy results in more relapses than extended radiotherapy for intracranial germinomas: modification in radiotherapy volume might be needed. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 71 (3): 667-71, 2008.

- Chen MJ, Santos Ada S, Sakuraba RK, et al.: Intensity-modulated and 3D-conformal radiotherapy for whole-ventricular irradiation as compared with conventional whole-brain irradiation in the management of localized central nervous system germ cell tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76 (2): 608-14, 2010.

- Joo JH, Park JH, Ra YS, et al.: Treatment outcome of radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: adaptive radiation field in relation to response to chemotherapy. Anticancer Res 34 (10): 5715-21, 2014.

- Rogers SJ, Mosleh-Shirazi MA, Saran FH: Radiotherapy of localised intracranial germinoma: time to sever historical ties? Lancet Oncol 6 (7): 509-19, 2005.

- Shikama N, Ogawa K, Tanaka S, et al.: Lack of benefit of spinal irradiation in the primary treatment of intracranial germinoma: a multiinstitutional, retrospective review of 180 patients. Cancer 104 (1): 126-34, 2005.

- Hardenbergh PH, Golden J, Billet A, et al.: Intracranial germinoma: the case for lower dose radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 39 (2): 419-26, 1997.

Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Childhood CNS Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for newly diagnosed childhood central nervous system (CNS) nongerminomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs) include the following:

- Chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy.

- Surgery, for tumors that partially respond to chemotherapy or for tumors that increase in size during or after therapy (possible growing teratoma syndrome).

The optimal treatment regimen for CNS NGGCTs remains unclear.

The prognosis for children with CNS NGGCTs is inferior to that for children with germinomas, but the difference is diminishing with the addition of multimodality therapy. NGGCTs are radiosensitive, but patient survival rates after standard craniospinal irradiation alone has been poor, ranging from 20% to 45% at 5 years.[

Chemotherapy Followed by Radiation Therapy

The use of chemotherapy before radiation therapy has increased survival rates. However, the specific chemotherapy regimen, length of therapy, and the optimal radiation field, timing, and dose remain under investigation.[

Evidence (chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy):

- A Children's Oncology Group (COG) study (ACNS0122 [NCT00047320]) evaluated neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy for children with localized NGGCTs.[

2 ] Neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisted of six courses with carboplatin/etoposide alternating with ifosfamide/etoposide. After chemotherapy was completed, responding patients received 36 Gy of craniospinal radiation therapy, with 54 Gy to the tumor bed.- On the basis of a central review, 87% of patients showed either partial response (PR) or complete response (CR).

- For the 102 eligible patients in the study, the 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rate was 84% (± 4%), and the OS rate was 93% (± 3%).

- At 3 years, the EFS rate was 92% and the OS rate was 98% for all patients who achieved CR or PR either after induction chemotherapy or with the absence of malignant elements documented during second-look surgery.

- The European SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 (NCT00293358) trial evaluated neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisting of four courses with cisplatin/etoposide/ifosfamide followed by focal radiation therapy (54 Gy) for patients with nonmetastatic disease.[

3 ]- Patients with localized tumors (n = 116) demonstrated 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates of 72% (± 4%) and OS rates of 82% (± 4%).

- Stratum 1 of the COG ACNS1123 (NCT01602666) study evaluated the efficacy of reduced-dose and reduced-volume radiation therapy in children and adolescents with localized NGGCTs who achieved PRs, CRs, and marker normalization after six cycles of chemotherapy. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of reduced radiation therapy on PFS, with a goal of preserving neurocognitive function. Isolated spinal relapses occurred in 10% of patients in this trial, causing early stoppage of the protocol. This is compared with 8% of patients who developed a similar pattern of relapse in the ACNS0122 (NCT00047320) trial.

Patients in this study received six cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide. If a CR or PR with or without second-look surgery was achieved, the patient was eligible for reduced radiation therapy, defined as 30.6 Gy to the whole-ventricular field and a 54-Gy boost to the tumor bed, compared with 36 Gy of craniospinal irradiation plus a 54-Gy tumor-bed boost used in the ACNS0122 trial.[

4 ,10 ]- Of the 107 patients enrolled, 66 (61.7%) achieved a CR or PR and received reduced radiation therapy. The 3-year PFS rate was 87.8% (± 4.04%), and the OS rate was 92.4% (± 3.3%).

- There were eight documented recurrences; six patients had distant spinal relapse alone and two patients had combined local-plus-distant relapse.

- Patients with localized NGGCTs who achieved a CR or PR with chemotherapy and received reduced radiation therapy had a good PFS rate, similar to patients in the ACNS0122 trial who received craniospinal irradiation.

- There was no significant difference in survival rates for NGGCT patients with localized disease in the two COG studies. The predominant site of relapse for patients in the ACNS1123 trial was in the spine, which was unique.[

2 ,4 ] - A subgroup analysis compared protons with photons to the whole ventricles for treating patients with NGGCTs.[

11 ] Mean radiation doses and the doses to 40% of volumes, including the supratentorial brain, cerebellum, bilateral temporal, parietal, and frontal lobes, were significantly lower among patients who were treated with protons than patients who were treated with photons. Late effects data confirming a clinical benefit are not available.

The current and prevailing controversy in the management of patients with newly diagnosed, localized NGGCTs—who have no evidence of dissemination and either a complete radiographic response to chemotherapy or have no evidence of disease before and after the initiation of chemotherapy—is the radiation volume. The SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 (NCT00293358) trial employed involved fields of radiation only for these patients with no radiographic evidence of residual or disseminated disease. Two COG protocols used either craniospinal or whole-ventricular fields of radiation plus a boost to the primary tumor. The incidence of isolated spinal relapses was similar in all of these studies, ranging from 8% to 11%.

Patients with relapsed NGGCTs are difficult to treat with curative intent, and their prognosis is guarded. Whether craniospinal irradiation or whole-ventricular plus spinal radiation should be included for all newly diagnosed NGGCT patients is an unresolved controversy and a major question for future clinical trials.

Surgery

A small percentage of patients treated with chemotherapy may have normalization of tumor markers with a less-than-complete radiographic response. Occasionally, a mass continues to expand in size even though tumor markers may have normalized. This condition, designated as growing teratoma syndrome, represents an accelerated growth of the mature teratoma components during or after treatment.[

A SIOP trial identified a significant OS advantage for patients without residual disease (5-year PFS rate, 85% ± 0.04% vs. 48% ± 0.07%), which underscores the important role of second-look surgery after chemotherapy and before irradiation.[

A second-look surgery can help determine whether the residual mass contains teratoma, fibrosis, or residual NGGCT.[

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Newly Diagnosed Childhood CNS NGGCTs

Early-phase therapeutic trials may be available for selected patients. These trials may be available via the

The following is an example of a national and/or institutional clinical trial that is currently being conducted:

- ACNS2021 (NCT04684368) (A Study of a New Way to Treat Children and Young Adults With a Brain Tumor Called NGGCT): This phase II trial studies the effect of chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy in treating patients with localized NGGCTs. The purpose of this study is to examine the tumor response to induction chemotherapy. Tumor response will then determine additional treatment options, including radiation therapy or high-dose chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant followed by radiation therapy.

References:

- Robertson PL, DaRosso RC, Allen JC: Improved prognosis of intracranial non-germinoma germ cell tumors with multimodality therapy. J Neurooncol 32 (1): 71-80, 1997.

- Goldman S, Bouffet E, Fisher PG, et al.: Phase II Trial Assessing the Ability of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy With or Without Second-Look Surgery to Eliminate Measurable Disease for Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 33 (22): 2464-71, 2015.

- Calaminus G, Frappaz D, Kortmann RD, et al.: Outcome of patients with intracranial non-germinomatous germ cell tumors-lessons from the SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 trial. Neuro Oncol 19 (12): 1661-1672, 2017.

- Fangusaro J, Wu S, MacDonald S, et al.: Phase II Trial of Response-Based Radiation Therapy for Patients With Localized CNS Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 37 (34): 3283-3290, 2019.

- Matsutani M; Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group: Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for CNS germ cell tumors--the Japanese experience. J Neurooncol 54 (3): 311-6, 2001.

- Calaminus G, Bamberg M, Jürgens H, et al.: Impact of surgery, chemotherapy and irradiation on long term outcome of intracranial malignant non-germinomatous germ cell tumors: results of the German Cooperative Trial MAKEI 89. Klin Padiatr 216 (3): 141-9, 2004 May-Jun.

- Baranzelli M, Patte C, Bouffet E, et al.: Carboplatin-based chemotherapy (CT) and focal irradiation (RT) in primary germ cell tumors (GCT): A French Society of Pediatric Oncology (SFOP) experience (meeting abstract). [Abstract] Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 18: A-538, 140A, 1999.

- Aoyama H, Shirato H, Ikeda J, et al.: Induction chemotherapy followed by low-dose involved-field radiotherapy for intracranial germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 20 (3): 857-65, 2002.

- Kim JW, Kim WC, Cho JH, et al.: A multimodal approach including craniospinal irradiation improves the treatment outcome of high-risk intracranial nongerminomatous germ cell tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84 (3): 625-31, 2012.

- Murphy ES, Dhall G, Fangusaro J, et al.: A Phase 2 Trial of Response-Based Radiation Therapy for Localized Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumors: Patterns of Failure and Radiation Dosimetry for Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 113 (1): 143-151, 2022.

- Mak DY, Siddiqui Z, Liu ZA, et al.: Photon versus proton whole ventricular radiotherapy for non-germinomatous germ cell tumors: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 69 (9): e29697, 2022.

- Kim CY, Choi JW, Lee JY, et al.: Intracranial growing teratoma syndrome: clinical characteristics and treatment strategy. J Neurooncol 101 (1): 109-15, 2011.

- Kong DS, Nam DH, Lee JI, et al.: Intracranial growing teratoma syndrome mimicking tumor relapse: a diagnostic dilemma. J Neurosurg Pediatr 3 (5): 392-6, 2009.

- Michaiel G, Strother D, Gottardo N, et al.: Intracranial growing teratoma syndrome (iGTS): an international case series and review of the literature. J Neurooncol 147 (3): 721-730, 2020.

- Oya S, Saito A, Okano A, et al.: The pathogenesis of intracranial growing teratoma syndrome: proliferation of tumor cells or formation of multiple expanding cysts? Two case reports and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 30 (8): 1455-61, 2014.

Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Childhood CNS Teratomas

Teratomas are designated as mature or immature on the basis of the absence or presence of differentiated tissues. The Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group stratifies teratomas for classification and intensity of treatment (chemotherapy and radiation) into a good-prognosis group (mature teratomas) and an intermediate-prognosis group (immature teratomas) (see Table 2), while the Children's Oncology Group includes immature teratomas with other nongerminomatous germ cell tumors.

Treatment options for newly diagnosed childhood central nervous system (CNS) teratomas include the following:

- Gross-total resection.

Gross-Total Resection

The primary treatment for teratomas is gross-total resection.[

Adjuvant treatment in the form of focal radiation therapy and/or adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with subtotally resected tumors is controversial. Small institutional series suggested a potential utility of stereotactic radiosurgery.[

References:

- Huang X, Zhang R, Zhou LF: Diagnosis and treatment of intracranial immature teratoma. Pediatr Neurosurg 45 (5): 354-60, 2009.

- Lee YH, Park EK, Park YS, et al.: Treatment and outcomes of primary intracranial teratoma. Childs Nerv Syst 25 (12): 1581-7, 2009.

Treatment of Recurrent Childhood CNS Germ Cell Tumors

Treatment options for recurrent childhood central nervous system (CNS) germ cell tumors (GCTs) include the following:

- Chemotherapy followed by additional radiation therapy.

- High-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue with or without additional radiation therapy.

For patients who had localized germinomas at diagnosis and were treated with craniospinal and local boost radiation therapy, the most common form of relapse is at the primary site.[

Patients with disseminated germinomas and nongerminomatous germ cell tumors (NGGCTs) also may have complex patterns of relapse, including local and/or disseminated intracranial or intraspinal relapse after treatment with craniospinal radiation therapy alone or preirradiation chemotherapy with various volumes and doses of radiation therapy.[

Enrollment on clinical trials should be considered for all patients with recurrent disease. Information about ongoing National Cancer Institute (NCI)–supported clinical trials is available from the

Chemotherapy Followed by Additional Radiation Therapy

Patients with germinomas that were treated initially with chemotherapy only can benefit from chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy at the time of relapse.[

High-Dose Chemotherapy With Stem Cell Rescue With or Without Additional Radiation Therapy

For patients with pure germinomas who previously received radiation therapy, myeloablative chemotherapy with stem cell rescue has been used. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue may also have curative potential for some patients with relapsed systemic NGGCTs.[

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Recurrent Childhood CNS GCTs

There are limited clinical trials available for patients with recurrent NGGCTs. Early-phase therapeutic trials may be available for selected patients. These trials may be available via the

References:

- Calaminus G, Kortmann R, Worch J, et al.: SIOP CNS GCT 96: final report of outcome of a prospective, multinational nonrandomized trial for children and adults with intracranial germinoma, comparing craniospinal irradiation alone with chemotherapy followed by focal primary site irradiation for patients with localized disease. Neuro Oncol 15 (6): 788-96, 2013.

- Calaminus G, Frappaz D, Kortmann RD, et al.: Outcome of patients with intracranial non-germinomatous germ cell tumors-lessons from the SIOP-CNS-GCT-96 trial. Neuro Oncol 19 (12): 1661-1672, 2017.

- Goldman S, Bouffet E, Fisher PG, et al.: Phase II Trial Assessing the Ability of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy With or Without Second-Look Surgery to Eliminate Measurable Disease for Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 33 (22): 2464-71, 2015.

- Merchant TE, Sherwood SH, Mulhern RK, et al.: CNS germinoma: disease control and long-term functional outcome for 12 children treated with craniospinal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 46 (5): 1171-6, 2000.

- Sawamura Y, Ikeda JL, Tada M, et al.: Salvage therapy for recurrent germinomas in the central nervous system. Br J Neurosurg 13 (4): 376-81, 1999.

- Hu YW, Huang PI, Wong TT, et al.: Salvage treatment for recurrent intracranial germinoma after reduced-volume radiotherapy: a single-institution experience and review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84 (3): 639-47, 2012.

- Murray MJ, Bailey S, Heinemann K, et al.: Treatment and outcomes of UK and German patients with relapsed intracranial germ cell tumors following uniform first-line therapy. Int J Cancer 141 (3): 621-635, 2017.

- Wong K, Opimo AB, Olch AJ, et al.: Re-irradiation of Recurrent Pineal Germ Cell Tumors with Radiosurgery: Report of Two Cases and Review of Literature. Cureus 8 (4): e585, 2016.

- Callec L, Lardy-Cleaud A, Guerrini-Rousseau L, et al.: Relapsing intracranial germ cell tumours warrant retreatment. Eur J Cancer 136: 186-194, 2020.

- Beyer J, Kramar A, Mandanas R, et al.: High-dose chemotherapy as salvage treatment in germ cell tumors: a multivariate analysis of prognostic variables. J Clin Oncol 14 (10): 2638-45, 1996.

- Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bosl GJ, et al.: High-dose carboplatin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide for patients with refractory germ cell tumors: treatment results and prognostic factors for survival and toxicity. J Clin Oncol 14 (4): 1098-105, 1996.

- Mabbott DJ, Monsalves E, Spiegler BJ, et al.: Longitudinal evaluation of neurocognitive function after treatment for central nervous system germ cell tumors in childhood. Cancer 117 (23): 5402-11, 2011.

- Acharya S, DeWees T, Shinohara ET, et al.: Long-term outcomes and late effects for childhood and young adulthood intracranial germinomas. Neuro Oncol 17 (5): 741-6, 2015.

Long-Term Effects of Childhood CNS Germ Cell Tumors

A significant proportion of children with central nervous system (CNS) germ cell tumors (GCTs) present with endocrinopathies, including diabetes insipidus and panhypopituitarism. In most cases, these endocrinopathies are permanent despite tumor control, and patients will need continuous hormone replacement therapy.[

Although significant improvements in the overall survival of patients with CNS GCTs have occurred, patients face significant late effects based on the location of the primary tumor and its treatment. These sequelae are not only limited to children, but they can also occur in adolescents and young adults. Treatment-related late effects include the following:

- Each chemotherapeutic agent has its own characteristic long-term side effects.

- Radiation therapy to the areas commonly affected by GCTs is known to contribute to a decline in patient performance status, visual-field impairments, endocrine disorders, learning disabilities, stroke, and psychiatric conditions.[

3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ,7 ,8 ,9 ] - Second tumors have been identified in this population, some of which are thought to be related to previous irradiation.[

8 ,10 ,11 ]

Current clinical trials and therapeutic approaches are directed at minimizing the long-term sequelae that result from the treatment of CNS GCTs.

For information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer, see Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

References:

- Rosenblum MK, Matsutani M, Van Meir EG: CNS germ cell tumours. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee WK, eds.: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous System. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2000, pp 208-14.

- Hoffman HJ, Otsubo H, Hendrick EB, et al.: Intracranial germ-cell tumors in children. J Neurosurg 74 (4): 545-51, 1991.

- Osuka S, Tsuboi K, Takano S, et al.: Long-term outcome of patients with intracranial germinoma. J Neurooncol 83 (1): 71-9, 2007.

- Balmaceda C, Finlay J: Current advances in the diagnosis and management of intracranial germ cell tumors. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 4 (3): 253-62, 2004.

- Odagiri K, Omura M, Hata M, et al.: Treatment outcomes, growth height, and neuroendocrine functions in patients with intracranial germ cell tumors treated with chemoradiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 84 (3): 632-8, 2012.

- Liang SY, Yang TF, Chen YW, et al.: Neuropsychological functions and quality of life in survived patients with intracranial germ cell tumors after treatment. Neuro Oncol 15 (11): 1543-51, 2013.

- Mabbott DJ, Monsalves E, Spiegler BJ, et al.: Longitudinal evaluation of neurocognitive function after treatment for central nervous system germ cell tumors in childhood. Cancer 117 (23): 5402-11, 2011.

- Acharya S, DeWees T, Shinohara ET, et al.: Long-term outcomes and late effects for childhood and young adulthood intracranial germinomas. Neuro Oncol 17 (5): 741-6, 2015.

- Wong J, Goddard K, Laperriere N, et al.: Long term toxicity of intracranial germ cell tumor treatment in adolescents and young adults. J Neurooncol 149 (3): 523-532, 2020.

- Jabbour SK, Zhang Z, Arnold D, et al.: Risk of second tumor in intracranial germinoma patients treated with radiation therapy: the Johns Hopkins experience. J Neurooncol 91 (2): 227-32, 2009.

- Sands SA, Kellie SJ, Davidow AL, et al.: Long-term quality of life and neuropsychologic functioning for patients with CNS germ-cell tumors: from the First International CNS Germ-Cell Tumor Study. Neuro Oncol 3 (3): 174-83, 2001.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

Latest Updates to This Summary (04 / 26 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Editorial changes were made to this summary.

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of childhood central nervous system germ cell tumors. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Childhood Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumors Treatment are:

- Kenneth J. Cohen, MD, MBA (Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital)

- Karen J. Marcus, MD, FACR (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children's Hospital)

- Roger J. Packer, MD (Children's National Hospital)

- D. Williams Parsons, MD, PhD (Texas Children's Hospital)

- Malcolm A. Smith, MD, PhD (National Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumors Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2024-04-26

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of New Mexico.